Today I am writing this post with ink, on paper. Much of my personal or creative writing is done this way. As opposed to Wendell Berry (a poet, novelist, and environmentalist), I do not rely on a wife, husband, or partner to type it up for me. I do that myself, at this very moment, by typing my handwritten thoughts directly into the Substack Editor (meta, right?). By doing so, my text goes through an invaluable editing process. Of course, I do use computers to write (hic!), but generally, only my less creative, less personal writing endeavours go straight to the screen and never see the light of actual day on paper (unless someone were to print it out afterwards - what a waste of rainforest that would be). The more personal a topic, the more likely I am to use an inkpen and paper.

If you have not yet heard of the 1987 essay “Why I am Not Going to Buy a Computer” by Wendell Berry, you can find it here. Last August I picked up a copy of his essay in a lovely Penguin Modern edition, and sat down to read it in a Japanese restaurant in the middle of Glasgow. Briefly put (too briefly, seriously, go read his essay), Berry explains why he personally does not see the appeal of using computers for his writing. Crucially, using a computer relies on resources that cost the earth and its inhabitants dearly, both for the electricity needed to run it, as well as its purchase, and re-purchase when the last model has become obsolete. But importantly, and this struck a chord with me, he rejects the notion that the computer as a writing tool is in and of itself superior to pen and paper, when it comes to the creative process. He argues, as long as no one has written anything better than any of the astounding works of literary art we had before Gates & Co., there is no reason to assume computers to be the superior writing tool. To me, his standpoint is not one of his reactionary anti-tech propaganda, but rather a keen observation. Not everyone will agree with me on that, and that is ok – we still live in a democracy, after all.

All of the reasons he stated almost 40 years ago apply, in my humble opinion, perfectly to the use of AI, and in particular large language models, today. Forty years later, we are not doing any better when it comes to carbon emissions1 or protecting the environment. On the contrary, we are finding ever new ways to burden our home planet, one of the more devastating flavours of the decade being the recreational use of large language models.

Let me start by saying that, to be a judge of the thing, I have used it. I have tested it in the ways I could think of, which are by no means excellent, exhaustive or innovative. I have used ChatGPT for embellishing never-ending cover letters when I was hunting for a job. I used image generators when they came out, for the pure novelty and entertainment of it, and long before, I was using machine learning approaches for my data analysis. The following critique is aimed largely at so-called creative use of generative AI and large language models. Machine learning itself is much older than when ChatGPT’s2 release started this craze of using some of the strongest computing tools we have to ask about the weather, in late 2022. Machine learning has important applications that can and do transform people’s lives for the better, such as when screening for tumors3, or decoding animal communication4. But I am willing to wager that the vast majority of everyday generative AI and large-language model (LLM) use is detrimental to our lives and the world we live in (and on).

Environmental and informational garbage

Aside from creating masses of pollution and environmental garbage5, large language models create a deluge of informational garbage - likely at least as damaging to our lives in the current political climate shift6. Generative AI does just what it is programmed to do: generate content that is appealing to its prompter, to keep them engaged and invested and increasingly reliant on the AI. Its primary goal is not to be truthful, but to always have an answer. When it doesn´t, it will invent, just like a talkative pupil that did not study for the oral exam, it will take snippets of what seems fitting, and regurgitate them. We do not notice this as often as it happens, because we enter our interactions with large language models with our own biases: usually, we ask AI about topics we do not know much about, to inform ourselves. Therefore, we are not capable of detecting cap7. If you do not believe me, try to talk with your preferred large language model about something you are intimately familiar with, like your home town, an obscure fanbase you follow, etc. I tried this recently together with a friend. Asking ChatGPT very subjective questions about my admittedly neither very exciting nor beautiful home town still yielded somewhat truthful results. (ChatGPT’s response on whether Bochum is a beautiful town was, effectively, “it depends what you consider beautiful”, indeed, very diplomatic). However, asking specifics (“Who was mayor in 1904?”, or “What are the best schools in town?”) quickly led to blatantly invented answers. Since I spent many years in that town, I was quickly able to see that the two schools it mentioned do not exist there (albeit in other German cities starting with B). It had me fooled for a second regarding the mayor, but when I asked it more detail about this supposed illustrious figure in Bochum´s history, it came back with “I am sorry, I have no records about this person - could you provide me with more info?”

Generative AI and large language models could be beautiful tools, but in the current misinformation age that we live in, they scare me enormously. (And I think this fear is very warranted). Another important bias we have to be aware of when using AI is the confirmation bias. The way I am asking a question can influence the AI, which after all, aims to please me, and lead it to selectively report on topics in a very one-sided manner. The extension of the social media echo-chamber. Our own confirmation bias8 can be particularly dangerous when we try to inform ourselves but only ask for one side of the coin, usually what we are already convinced about.

Why am I not going to use generative AI for writing?

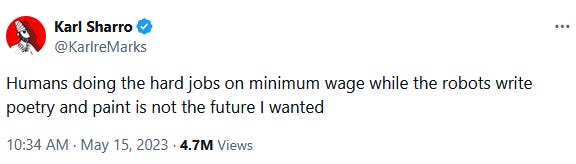

Writing on a computer means it is less effortful to bring words down, it is faster, and more legible than wielding a pen. It also affords you to move, copy, cut ad libitum. Therefore, writing on a computer is more forgiving, and makes it so that you can think less about what you are going to say. Because you can unsay, resay, reorder, rephrase so easily. AI removes even more of the thinking and effort: now, it is not just easier to rewrite, but I do not even have to do it anymore. There is not just less effort, but no effort, and no thinking for myself involved anymore. And I fear, personality in writing is lost completely.

When I write, I want it to be an expression of my own thoughts, not those of an AI. I want my effort, my blood, sweat, and tears to show – and be admired or discredited accordingly. If I fail, at least I will have failed on my own. If I succeed, I will know: this was me, my thoughts and ideas, that made it. Some of my students and users of AI do not care about writing, they have no personal investment and wish to be good at it. However, I cannot help but wonder: will a good grade gotten with the help of AI mean as much to them, as if they had achieved it on their own? Will younger people be deprived the tremendous joy of noticing oneself getting better, through effort? And will future generations not even know they are missing out on this joy of improving, of getting it, on your own? Will fewer and fewer people turn to pen and paper to express themselves?

And here is another thing to be-(a)ware of: when you use AI, you are using someone else´s work, someone else´s effort, without their consent and often without relying on your own work, brain, and effort. Whenever an LLM or generative AI generates an image for you, or a poem, or an idea for a novel or…, you have to be aware that some of it is plagiarism, plain and simple, especially since you cannot cite your (or rather the AI´s)9, and rarely cite ChatGPT itself.

Personally, I would rather look at a painting by someone with mediocre technical skill, but a someone with wishes, desires, intentions that they poured into their art. Likewise I would rather read a poem with some clunky passages that was written by a young adult, expressing their experience in the world, than the most polished artworks chiselled out of billions of unwitting source materials, simply made to appeal to me for 5 seconds, not to express something otherwise inexpressible, before I move onto the next prompt.

For these reasons mainly, the informational and environmental garbage, the loss of individuality, effort and learning, the threat of echo-chambering myself, and the danger all of our brittle democracies currently face, amplified by large language models, I do not wish to use these tools to supposedly gain ease and entertainment. I will not always succeed, but I will try. For me personally, using large language models for my own writing is completely counter to my own motivations and aspirations: I like writing, so why would I outsource this favourite part of my job to a machine? But it is also counter to what I believe one of the true purposes of writing to be: self-expression.

Looking back at the 1987 essay, not many people followed Wendell Berry in his pursuit. When I revisit my essay in 2063, maybe it will have aged poorly (and it may well do so even sooner). Maybe I will have betrayed my own resolutions and opinions. Still, we should think about what we want to use generative AI for, and what not. We should draw our own lines of the costs we may consider too dear to pay, for another profile picture in the style of some creative mastermind that we do not believe ourselves to be.

The further crumbling of environment, the rise of populism, and the diminishing value of each of our creative endeavours – I consider these prices to be too high for whatever it is that ChatGPT has to offer.

see: “Data Page: Carbon dioxide emissions by income level”, part of the following publication: Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado, and Max Roser (2023) - “CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”. Data adapted from Global Carbon Project. Retrieved from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250716-155402/grapher/co2-income-level.html [online resource] (archived on July 16, 2025).

Note: I do not wish to single-out ChatGPT as the sole wrongdoer. I am merely using it as an exemplar, as it is the most broadly known. The tool itself, again, may not be at fault. The issue is how carelessly it is being used by us.

See: Raghavendra, U., Gudigar, A., Paul, A., Goutham, T. S., Inamdar, M. A., Hegde, A., Devi, A., Ooi, C. P., Deo, R. C., Barua, P. D., Molinari, F., Ciaccio, E. J., & Acharya, U. R. (2023). Brain tumor detection and screening using artificial intelligence techniques: Current trends and future perspectives. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 163, 107063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107063

and: Wei, M. L., Tada, M., So, A., & Torres, R. (2024). Artificial intelligence and skin cancer. Frontiers in medicine, 11, 1331895., as examples.

See: Rutz, C., Bronstein, M., Raskin, A., Vernes, S. C., Zacarian, K., & Blasi, D. E. (2023). Using machine learning to decode animal communication. Science, 381(6654), 152–155. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg7314

and: Ryan, M., & Bossert, L. N. (2024). Dr. Doolittle uses AI: Ethical challenges of trying to speak whale. Biological Conservation, 295, 110648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110648, as examples.

Already, bots are making up more than half of ALL of the internet traffic, it seems: https://www.independent.co.uk/tech/bots-internet-traffic-ai-chatgpt-b2733450.html , based on this: https://www.imperva.com/resources/resource-library/reports/2025-bad-bot-report/ report, by Imperva, a US-American IT Security company.

A typo here initially resultet in me omitting the “f” in the last word. That was probably not a coincidence.

Talking about shit, did you know, most AI company logos look like buttholes? https://velvetshark.com/ai-company-logos-that-look-like-buttholes

Despite being a millenial, I had to include this Gen Z slang for “lie”, purely because of the alliteration. Excuse me if I am being “cringe”.

Find some useful information on the confirmation bias here: https://www.scribbr.com/research-bias/confirmation-bias/

Check out this blogpost by Lizzie Wolkovich from the University of British Columbia, talking about why she is choosing not to chair student defenses anymore, when their works are written with/by AI. She raises another important argument why AI should not be used as a student or anyone in training, which to me can be summarized as respect towards the work and towards supervision/proofreading. But she also illustrates some of the reluctance in the field to cite ChatGPT, although her (and some universities´) guidelines can be quite clear.